Wednesday, May 16, 2012

Lunch With a Proper Artist

2009

It is always a welcome opportunity to cut through the cultural garbage with my former professor N-, a very successful painter who taught for decades and whose work is collected like free drinks at a heartbreak hotel. His work is keenly observational and yet almost wholly invented, a bit like the Yale artist William Bailey and his deceptively simple but deeply mysterious still lifes.

I particular appreciate his what you might call millennial perspective on visual art, art rolling in ribbons of rhyming cycles through history, far more coherent and conversational -over centuries- than the present fashion's interpretation, which assumes that context is so complex and powerful that art appears as a mere illustration of a certain ephemeral nexus of deterministic cultural factors. Well - duh. If I may be allowed (and I am) a caricature of contemporary art interpretation, it feels like there has been a long campaign among intellectuals to regard artists as globs of clay, their work wholly formed by cultural, economic and political circumstance, and that as that circumstance changes, their work cannot be understood except with a complete accounting of those circumstances. The implication is that the work has no particular value without historical interpretation.

Fine analysis, if you are getting paid for historical interpretation.

By contrast, N- reads art history as more of a dynamic conversation among artists living in different times, a multi-sided conversation until someone dies, and even then, there is an unending visual multi-lectic. I find myself much closer to this view - I start off every drawing class with the 70, 000 year old image from the Blombos cave in South Africa, which has soaked into compositional structures in my work. But the real point is in his phrase - artists speak to each other across centuries.

It's interesting that in such a technically skilled painter, he makes an absolute distinction between art and rendering, rendering, in my phrase, simply being the grammar of visual art, which like English grammar must be mastered but never confused for the end itself. It's fun hearing him on Bouguereau, the brilliant but endlessly cheesy villain representing the 19th century French Academy, sort of the Evil Empire compared to the liberating rebels of the Impressionists: N- points to the absolute technical genius: maybe the best in all of painting history in painting light on flesh, and in spite of this, it will never really be rehabilitated as high art. Yet even here, the Impressionists desperately wanted the validation of the academy, and the academicians were adopting techniques from the rebels; John Singer Sargent, the powerful American portraitist of the aristocracy, did impressionistic, cutting edge works of breathtaking gestural power and saturated color, while his portraits veered from obsequious money-makers to among the most brilliant.

What capitalizes art as Art is a serious philosophical ambition combined with the technical mastery and imagination to uncover and execute it. Far, far from a complete definition, but that element is true anywhere, at any point in history. Good work is rich, essentially inexhaustible in its viewing. There are any number of strategies to get there, but what makes artwork powerful, interesting and irreplaceable is incredibly fragile; a flat note in it's symphony can erase all that was done. This is why 90% of the stuff in the galleries lays there like a lump (worse, a pretentious lump) and even the greatest artists have piles of terrible work.

One of N-'s essential points is that the driving principles of effective artwork are remarkably simple, and they tie together artists as diverse as Andrew Goldsworthy (N- once essentially called this stuff Design 101 with sticks) and Damien Hirst (the half-a-cow in formaldehyde guy). The push and pull of attraction and repulsion, the conscious manipulation of spatiality, a practiced but straightforward understanding of color and line, an understanding of the difference between what is and what people see (there are no lines as such in nature, but we see lines everywhere, symbolic boundaries between intrinsic natures of things perceived.) People are fascinated, have always been fascinated, by the juxtaposition of geometric forms on organic forms, and vice versa. Simple, like the 12 musical notes. Infinitely complex, like arranging 12 musical notes.

It would be very easy to dismiss all this conservative; that would be a red herring. N- says"the avant-garde is a very crowded place," and in the contemporary art world, with a genuine and truly unprecedented flourishing of all art forms, in all kinds of media and all their intersections, enormous, grant-drunk, gate-keeping institutions are camped on that line like Star Wars fans in tailored grey Channel suits, waiting for the next new opening, and usually getting "Attack of the Clones" for their trouble. That's what you get for dismissing authorship as essential to art-making. Now the simpering Soho dandies will have to live with their BX Haus 211B art robots.

But N-'s last observation cut through. He just drove to Alaska last summer, primarily in the Interior around Fairbanks. What left the greatest impression on this landscape painter , the unreal majesty of Denali, the foraging grizzly bears, the mighty Yukon?

"I think those must be the fattest people I've ever seen."

"Art will cease to be political when reality ceases to be political."

April 12, 2011

"Art will cease to be political when reality ceases to be political."

- NYT Reader comment on the Ai Weiwei detention story in China. Not to say Art MUST be political. But as a social practice by many people, it will be, and a free practice is, we trust, it is vastly better.

Another interesting reader comment:

"(in the West) We don't call it "censorship;" instead we say something like "the market isn't interested/it won't make money....See Jeff Koons, and a long list of other trivial, highly marketable 'artists' who are not only accepted, but heavily promoted - precisely because while they may seem culturally outrageous, they are politically harmless. "

It may surprise you to learn of the huge commercial success of avant-garde art in China - but the arrest of Ai- a big deal- changes much. Art can be commercial, poetic, it can edgy, or political, or all of these. To the Chinese dictatorship, edgy is great: it gains prestige and business. (As it does here.) But political is a crime. This underscores the incredible potential and emptiness of much contemporary work.

The severe suppression of a painter's Chen Guang's work two years ago- his work on Tienanmen Square was not just censored but nearly eradicated from the Internet - while edgy performance and situationist styles flourished in China, suggested to me that painting what's in front of your nose with courage is still one of the most uncontrollable, powerful art forms.

And finally, I am deeply disappointed in the tone of all the commenters in the articles. None of these professors and curators of Asian Art and political affairs, stands up and says: China's arrest of Ai is wrong, it is meant to crush free thinking, it hurts both China's growing culture and international standing, and China must be pressured to release him. Several weakly imply it.

I tire greatly of balanced, reasonable deference to dictators.

Aspiring Artists and Puppies

2006 (essay response)

I brought Rilke up -a little lazily -because that confession in the night question is the still the key question to reassure the serious and challenge the art puppies nipping at the socks.

It's important to remember, as late stage capitalism threatens to make Blade Runner look like It's a Wonderful Life, that the urge to create is nearly universal among people, and the mere fact we channel it into shopping and commodified labor says nothing about our capabilities, only our vulnerabilities. (And as I write this in the cafe, there is literally a table of marketers next to me "trying to adopt the artistic mind-set process," underscoring non-profit organization "social networks'" "psychodemographics as opposed to demographics." And now the guy pretending to have the magic of artistic process just dropped the word the word "mindshare," and connected it to "community." I am restraining myself with some difficulty, imagining as I am the perfect "Clop" and tinkling sound my cracking the coffee cup over his head would make, not to mention the screaming. "We need to bring people together in real ways." Every second of this endless self-congratulatory greedy drivel is pushing me I ask myself: What Would Utah Phillips do? Probably whack them with that "sockful of puppy shit we call a culture.")

Art, - as profession and sublimity - is a special case of creativity, when it is pursued to an obsessive degree from a repeated impulse of individual necessity toward the exploration of the baroque permutation of truths observed and worked from within specific phenomena, often, in the case of painting and sculpture, by thinking within the phenomenology of material. Draw, write, compute, re-create -expand the envelope of what can be known and what is possible through explorative action, communicate it, and you've struck something that could be Art. Even Science may be a special case of Art - the same impulses drive it, the same obsessive observation, the same bringing of nothing into knowing. Art is freed of necessary function, but by giving up universal clarity, it is capable of attempting to track the whole impulse of the human mind at once.

But we all crave making. I wandered into the ceramics studio the other days and threw about 6 pots - satisfying, mediocre pots....a lot of people there, smart students otherwise, poking and pounding clay like six year olds. Something about it, ceramics at college, usually a stand in joke for misplaced pride in a lopsided ashtray, something about it that stands in for what people can't be anymore without being hobbyists: harmless, neuter, unmarketable, irrelevant.

So many people face an endless, dreamless bureaucratic life - and there so many gatekeepers to Art, of which I'm a minor one, so many reasons to wither at 19. (Kids these days: smart and meek and betrayed by our convenience, with their abilities to build and give less relevant to our markets that their manufactured desires.)

I believe there are plenty of good poets - more than ever, I suspect, like good musicians and artists, but even the greatest mastery cannot much stir a world producing endless fountains of Product. Art exists when a hair goes to one side of a blade, and not the other, and it's intrinsic delicacy makes it extremely fragile. I think the kind of obsessively clean, minimalistic, cold and empty style which has dominated since Warhol is an embrace of delicate futility, where presenting the simple absence of social noise is considered sufficient to be artistic.

The aspirants have even less chance than the students or the masters, but they will be rewarded, oh so rewarded, for making the right purchase.

But those endless schools of would be poets and writers and artists and physicists (yes it must be said - physics and mathematics as philosophy is just as highly impractical a career choice) are coming from people who are taught that their fundamental abilities are completely replaceable, our communities are interchangeable, and their lives are best lived in constant worry, false certainty, and commodified desire. Who wouldn't want an alternative? Art seems like an out - so does music, so do sports-to act, to be human, to be individually recognized. Your disposable life at Best Buy isn't gonna cut it. Facing their disposability, interchangeability and their individual irrelevance before mass culture, why not try, try to be an artist, a rock star, a poet, a B-Ball god, an evangelist zombie, or Paris Hilton? If the society teaches you that your already reified labor is done more cheaply by even more anonymous people in even more anonymous places, if it cannot offer you a place, a reasonable sense of meaning and identity, what is your plan?

Today, you can even forget trying to go into single family farming in America. Finally, we're weeding out those lazy bastards and their gold-bricking economic inefficiencies.

But in the modern world, the outs are also are professionalized social roles, wholly capitalist creatures, and it's hardly a new observation that in non-industrial societies art, music, politics, poetry, games, hunting, gathering, making and spirituality were done by nearly all and share a particular quality of full expression and participation - and aside from endless centuries of poverty, uncertainty and iron-clad social roles, it's kind of appealing.

I'm not an anarchist (or AM I?) but all this techno-industrial candy, with all its promise, is not making us our best selves. Polls pointing to growing social isolation and expressions of intense American loneliness do not bode well.

Witness the absurd - and dangerous and historically recent - rise of fundamentalism in so many religions- which is partly, I think, a toxic reaction to the disease of social isolation. That disconnect is felt with particular intensity among young 2nd generation Muslims in Europe, and we're seeing the results.

But Americans are feeling a version of the same thing, good old-fashioned alienation with a new intensity from mass-culture, ubiquitous marketing, dissolution of community, and escalating economic insecurity. They turn to art, to religion, to fantasy, to truly impossible dreams of celebrity or riches.

Interesting, just Friday, I happened to walk into a bookstore on Capitol Hill and bought The White Goddess; perhaps pre-industrial societies were better at creating a sense of our meaning.

I don't say go back. I do say: look out.

I brought Rilke up -a little lazily -because that confession in the night question is the still the key question to reassure the serious and challenge the art puppies nipping at the socks.

It's important to remember, as late stage capitalism threatens to make Blade Runner look like It's a Wonderful Life, that the urge to create is nearly universal among people, and the mere fact we channel it into shopping and commodified labor says nothing about our capabilities, only our vulnerabilities. (And as I write this in the cafe, there is literally a table of marketers next to me "trying to adopt the artistic mind-set process," underscoring non-profit organization "social networks'" "psychodemographics as opposed to demographics." And now the guy pretending to have the magic of artistic process just dropped the word the word "mindshare," and connected it to "community." I am restraining myself with some difficulty, imagining as I am the perfect "Clop" and tinkling sound my cracking the coffee cup over his head would make, not to mention the screaming. "We need to bring people together in real ways." Every second of this endless self-congratulatory greedy drivel is pushing me I ask myself: What Would Utah Phillips do? Probably whack them with that "sockful of puppy shit we call a culture.")

Art, - as profession and sublimity - is a special case of creativity, when it is pursued to an obsessive degree from a repeated impulse of individual necessity toward the exploration of the baroque permutation of truths observed and worked from within specific phenomena, often, in the case of painting and sculpture, by thinking within the phenomenology of material. Draw, write, compute, re-create -expand the envelope of what can be known and what is possible through explorative action, communicate it, and you've struck something that could be Art. Even Science may be a special case of Art - the same impulses drive it, the same obsessive observation, the same bringing of nothing into knowing. Art is freed of necessary function, but by giving up universal clarity, it is capable of attempting to track the whole impulse of the human mind at once.

But we all crave making. I wandered into the ceramics studio the other days and threw about 6 pots - satisfying, mediocre pots....a lot of people there, smart students otherwise, poking and pounding clay like six year olds. Something about it, ceramics at college, usually a stand in joke for misplaced pride in a lopsided ashtray, something about it that stands in for what people can't be anymore without being hobbyists: harmless, neuter, unmarketable, irrelevant.

So many people face an endless, dreamless bureaucratic life - and there so many gatekeepers to Art, of which I'm a minor one, so many reasons to wither at 19. (Kids these days: smart and meek and betrayed by our convenience, with their abilities to build and give less relevant to our markets that their manufactured desires.)

I believe there are plenty of good poets - more than ever, I suspect, like good musicians and artists, but even the greatest mastery cannot much stir a world producing endless fountains of Product. Art exists when a hair goes to one side of a blade, and not the other, and it's intrinsic delicacy makes it extremely fragile. I think the kind of obsessively clean, minimalistic, cold and empty style which has dominated since Warhol is an embrace of delicate futility, where presenting the simple absence of social noise is considered sufficient to be artistic.

The aspirants have even less chance than the students or the masters, but they will be rewarded, oh so rewarded, for making the right purchase.

But those endless schools of would be poets and writers and artists and physicists (yes it must be said - physics and mathematics as philosophy is just as highly impractical a career choice) are coming from people who are taught that their fundamental abilities are completely replaceable, our communities are interchangeable, and their lives are best lived in constant worry, false certainty, and commodified desire. Who wouldn't want an alternative? Art seems like an out - so does music, so do sports-to act, to be human, to be individually recognized. Your disposable life at Best Buy isn't gonna cut it. Facing their disposability, interchangeability and their individual irrelevance before mass culture, why not try, try to be an artist, a rock star, a poet, a B-Ball god, an evangelist zombie, or Paris Hilton? If the society teaches you that your already reified labor is done more cheaply by even more anonymous people in even more anonymous places, if it cannot offer you a place, a reasonable sense of meaning and identity, what is your plan?

Today, you can even forget trying to go into single family farming in America. Finally, we're weeding out those lazy bastards and their gold-bricking economic inefficiencies.

But in the modern world, the outs are also are professionalized social roles, wholly capitalist creatures, and it's hardly a new observation that in non-industrial societies art, music, politics, poetry, games, hunting, gathering, making and spirituality were done by nearly all and share a particular quality of full expression and participation - and aside from endless centuries of poverty, uncertainty and iron-clad social roles, it's kind of appealing.

I'm not an anarchist (or AM I?) but all this techno-industrial candy, with all its promise, is not making us our best selves. Polls pointing to growing social isolation and expressions of intense American loneliness do not bode well.

Witness the absurd - and dangerous and historically recent - rise of fundamentalism in so many religions- which is partly, I think, a toxic reaction to the disease of social isolation. That disconnect is felt with particular intensity among young 2nd generation Muslims in Europe, and we're seeing the results.

But Americans are feeling a version of the same thing, good old-fashioned alienation with a new intensity from mass-culture, ubiquitous marketing, dissolution of community, and escalating economic insecurity. They turn to art, to religion, to fantasy, to truly impossible dreams of celebrity or riches.

Interesting, just Friday, I happened to walk into a bookstore on Capitol Hill and bought The White Goddess; perhaps pre-industrial societies were better at creating a sense of our meaning.

I don't say go back. I do say: look out.

Robert Hughes and What You Might Call Your Art There

Explain your bad art to this face.

Robert Hughes serious, hilarious and readable Time art critic for many years, has a new autobiography. (NYT) The Washington Post review is more to the point.

Comparing the careers of J. Seward Johnson Jr. and Jeff Koons, he once said, was like debating the merits of dog excrement versus cat excrement — although Mr. Hughes would never use a word as flat and unevocative as excrement.

Hughes wrote the definitive, argumentative, popularizing work on the rise of modernism, Shock of the New, with it's famous attacks on Brasila,( a critique I share) and Picasso's Guernica (as a triumph of style over substance, even of a Nazi air raid, an understandable critique I don't share) He has long been a welcome antidote to ever-higher piles of ideological garbage in art, a rejection of the primacy of the word.

But he is far more than a contrarian:

"Art, I now realized, was the symbolic discourse that truly reached into me -- though the art I had seen and come to know in Australia had only done this intermittently and weakly. It wasn't a question of confusing art with religion, or trying to make a religion out of art. As some people are tone-deaf, I was religion-deaf, and in fact I would have thought it a misuse, even a debasement, of a work of art to turn it into a mere ancillary, a signpost to some imagined, hoped-for, but illusory experience of God. But I was beginning, at last, to derive from art, from architecture, and even from the beauty of organized landscape a sense of transcendence that organized religion had offered me -- but that I had never received."

Fine Hughes quotes:

The greater the artist, the greater the doubt. Perfect confidence is granted to the less talented as a consolation prize.

Lines, Molecules and Metaphors of Painting 2006

If you ever sat still long enough near me, you probably will have heard me talk about material and illusion and information and time as a source for painting. What's below is not news to anyone doing animation, or anyone pursuing mathematical topology modeling for a living, or probably anyone who's read Tufte's classic The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, except for the end result.

I was sketching a little graphic today, somewhat like one of these: {

Then I doubled it: {}

I then treated it in three dimensions, building this shape on the full xyz axis, on paper, sketching out the results, adding another, adding another. It builds into kind of "spin." When you spin it on one axis you get a solid shape, sort of a like a sphere with a brim. A two axis spin is even more interesting.

The process of drawing the spin of this {} fits neatly into a model of the operation of the natural progression of time on a line shape. I take a 2 dimensional shape and twirl it, and as I draw more positions of the shape in illusionistic 3-d space, the shape becomes a solid, each step adding more material, each illusion I add representing another step in the progression of time.

The idea is clearly fundamental to animation. But animation is also presented in a strip of time, for the purpose of presenting a direct illusion of reality - the still images with a series turns into the illusion of the passage of time. It's almost a primary application of digital imaging technology to do this precisely and cheaply.

What was beginning to be interesting to me here was sort of the reverse - the strip of time represented by the still image. The act of drawing the image involves time, adding each new {}, and the progression of one position of the {} to the next on the z axis IMPLIES and can only be the result of the passage of time. The still result, however, is an unmoving three dimensional solid, a 3-d shape almost exactly like an old metal float.

I backed up a little at this point. In a revelation for someone who last did calculus or ceramics 20 years ago, and never took topology, I re-realized that any line that was NOT straight, once spun through time, would create a three dimensional shape, a little like a Spirograph. If the line was straight you could get a flat circle by twirling it on the other axis.

Spin out any slight flaw in a line and you get a volume.

(About a year ago I got to play with a rapid prototyper and made a mathematical object that was the institial space between a regular stacking of spheres. This suggests a project of hand drawing straight lines, scanning the results, spinning them in Rhino or a similar program, and making the thin, irregular, semi cylindrical object on a prototyper. Or, save the $750,000 equipment costs and do it on a lathe. New prototypers are truly incredible.)

I can report that an interesting problem in formal topology was recently solved by a glass blower, something that really should not surprise you- material teaches when symbology stutters. But I'm going down this road for a different path - the irreducibly human: our perception of time passing, immediate past memory and anticipation of human presence, how nothing spins into something - a visual analogy to the popular summaries of string theory (see above on scraping through calculus) which suggest collisions of fields that twist and spin into stuff.

Painting can be the static image that is the spoor of these machinations, distinct, because it only forms through human consciousness and the twists and spins the body's action forms on material. In the act of painting is the static footprint in the mud of absence spinning into presence slowing into absence, and importanry to me, it occurs at the natural pace of human consciousness, which of course is a constantly evolving state, from a shade of blue to a Monkees riff to my arm itches to an irrational desire for twinkies.

The final analogy here was thinking of space-time spinning an empty volume into stuff, a mass of some kind. I suppose there are physicists who can tell me whether mass exists without time, but my suspicion is that mass without time would have no applicable meaning.

Allow me to leap to the metaphor of the molecule: and old definition of which is the smallest part of substance which has all the characteristics of that substance. Here is where I'm tying this together: a successful painting, or artwork of any kind, is a molecule of a much larger substance. In the case of painting, I'm using substance to mean the stuff of human experience (this is my metaphor and I can do what I want) - substance as a combination of material, the illusions the material creates, the physical object of the painting's relationships to all its spiritual, political, perceptual, personal implications, the way this wholly dependent on the human natural and cultural biases in perceiving those illusions.

A good painting -any good artwork - is something irreducibly "true," a single molecule of big stuff, containing what you need to know about that stuff, but unable to show the vastness of it's totality across time, distance, and human consciousness. A great work, say Brughels's 99 Netherlandish Proverbs, gives you untold volumes of information about time and experience not shown in the work, stories and smells and the plays of light and personality before the moment of the image and inevitable in the future. It is just as true of Rothko's color field paintings, which boil beautifully before your eyes, touching the spiritual impulse.

So an analogy of good art might be this: an illusionary process or object, cleaned of the extraneous, whose quality is proportional to the richness and penetration of all its implications. A single molecule of the big stuff.

Why illusionary? It has to be. Truth never reveals itself without a fight in the shadows.

I was sketching a little graphic today, somewhat like one of these: {

Then I doubled it: {}

I then treated it in three dimensions, building this shape on the full xyz axis, on paper, sketching out the results, adding another, adding another. It builds into kind of "spin." When you spin it on one axis you get a solid shape, sort of a like a sphere with a brim. A two axis spin is even more interesting.

The process of drawing the spin of this {} fits neatly into a model of the operation of the natural progression of time on a line shape. I take a 2 dimensional shape and twirl it, and as I draw more positions of the shape in illusionistic 3-d space, the shape becomes a solid, each step adding more material, each illusion I add representing another step in the progression of time.

The idea is clearly fundamental to animation. But animation is also presented in a strip of time, for the purpose of presenting a direct illusion of reality - the still images with a series turns into the illusion of the passage of time. It's almost a primary application of digital imaging technology to do this precisely and cheaply.

What was beginning to be interesting to me here was sort of the reverse - the strip of time represented by the still image. The act of drawing the image involves time, adding each new {}, and the progression of one position of the {} to the next on the z axis IMPLIES and can only be the result of the passage of time. The still result, however, is an unmoving three dimensional solid, a 3-d shape almost exactly like an old metal float.

I backed up a little at this point. In a revelation for someone who last did calculus or ceramics 20 years ago, and never took topology, I re-realized that any line that was NOT straight, once spun through time, would create a three dimensional shape, a little like a Spirograph. If the line was straight you could get a flat circle by twirling it on the other axis.

Spin out any slight flaw in a line and you get a volume.

(About a year ago I got to play with a rapid prototyper and made a mathematical object that was the institial space between a regular stacking of spheres. This suggests a project of hand drawing straight lines, scanning the results, spinning them in Rhino or a similar program, and making the thin, irregular, semi cylindrical object on a prototyper. Or, save the $750,000 equipment costs and do it on a lathe. New prototypers are truly incredible.)

I can report that an interesting problem in formal topology was recently solved by a glass blower, something that really should not surprise you- material teaches when symbology stutters. But I'm going down this road for a different path - the irreducibly human: our perception of time passing, immediate past memory and anticipation of human presence, how nothing spins into something - a visual analogy to the popular summaries of string theory (see above on scraping through calculus) which suggest collisions of fields that twist and spin into stuff.

Painting can be the static image that is the spoor of these machinations, distinct, because it only forms through human consciousness and the twists and spins the body's action forms on material. In the act of painting is the static footprint in the mud of absence spinning into presence slowing into absence, and importanry to me, it occurs at the natural pace of human consciousness, which of course is a constantly evolving state, from a shade of blue to a Monkees riff to my arm itches to an irrational desire for twinkies.

The final analogy here was thinking of space-time spinning an empty volume into stuff, a mass of some kind. I suppose there are physicists who can tell me whether mass exists without time, but my suspicion is that mass without time would have no applicable meaning.

Allow me to leap to the metaphor of the molecule: and old definition of which is the smallest part of substance which has all the characteristics of that substance. Here is where I'm tying this together: a successful painting, or artwork of any kind, is a molecule of a much larger substance. In the case of painting, I'm using substance to mean the stuff of human experience (this is my metaphor and I can do what I want) - substance as a combination of material, the illusions the material creates, the physical object of the painting's relationships to all its spiritual, political, perceptual, personal implications, the way this wholly dependent on the human natural and cultural biases in perceiving those illusions.

A good painting -any good artwork - is something irreducibly "true," a single molecule of big stuff, containing what you need to know about that stuff, but unable to show the vastness of it's totality across time, distance, and human consciousness. A great work, say Brughels's 99 Netherlandish Proverbs, gives you untold volumes of information about time and experience not shown in the work, stories and smells and the plays of light and personality before the moment of the image and inevitable in the future. It is just as true of Rothko's color field paintings, which boil beautifully before your eyes, touching the spiritual impulse.

So an analogy of good art might be this: an illusionary process or object, cleaned of the extraneous, whose quality is proportional to the richness and penetration of all its implications. A single molecule of the big stuff.

Why illusionary? It has to be. Truth never reveals itself without a fight in the shadows.

Anselm Kiefer: When I was Four I Wanted to be Jesus

May 21, 2008

While looking for contacts with European artists about the B-17 project - I found this excellent interview with Anselm Kiefer by Sean O'Hagan, who more and more represents to me what art must be today.

His mentor was Joseph Beuys, who once famously explained art history to a dead rabbit in a three day gallery exhibition, and who later founded the German Green Party.

I am fond of artist interviews: art prose tends to be unreadable, either fawning, dry or cynical.

His show that toured through S.F. a couple years ago, the maddeningly ambitious, intelligent and emotional Heaven and Earth, is I think one of the great cultural works of contemporary art. It would have been easy for him to join the massed millions in the lightly ironic Pop Army, but he bucked every trend, progressive in politics, conservative of art's real power.

Below, O'Hagen describes paintings from my favorite series - monumental paintings of the open ocean - in Leviathan, a lead U-Boat hangs just above the sea. (One note here - I'm not sure that any artist's work looks worse on the internet than Kiefer's compared to its actual appearance. It will look muddy and scattered and unreadable in many of the images- this is emphatically NOT the case in person. )

Kiefer's sea is a huge, brooding ocean, grey-black, turbulent, thunderous. Up close, the crashing waves seem like solid ripples of congealed oil so thick are the layers of paint - and what looks like encrusted earth - that have been applied to the canvas. The paintings are so elemental, so humming with raw energy, that you can almost hear the ocean's roar in this big cavernous room. There are echoes, too, of other seascapes, of Turner, of course, and Courbet.

'Yes! Yes!' says Kiefer, nodding his head vigorously. 'You do the sea and Turner is there, always.' I ask him if, given his prodigious output, he discards many works along the way. 'Many, yes. But then I go over them. A painting is a conglomeration of failings. But, we can say this of life also.'

He laughs and then quickly turns serious again. 'The making of a painting,' he continues, 'is a reflection of your thought process but it also has a process of its own. Always, it is about somewhere I am trying to get to that I can never get to. This is the dilemma. But you also reach a place of transformation. The painting is transformed and you are transformed also. This is the exciting part.

Turner - that made me happy, it was my second thought looking at these pieces. The first was that it felt more like being on the sea that any painting I've ever seen .

In particular, he had delved deep into what it means to be German, and poked around in the open wounds from the War in order to find a path out of unimaginable horror, a horror which had to not just be confronted but engaged.

It is not a minor point that American artists must too regard our recent history with open eyes, and find a path to our best selves. We have an odder task than German artists. Americans would confront self-concept of heroism in that same, infinitely bloody war, and in present war. Superficially, that is easier.

But war by nature mixes heroism and brutality- the means which serve the hero and the villain were not greatly different. I read the account of one B-17 pilot who said, after much agonizing over the shift in targeting toward the destruction of cities, that there was one salvation for such horror: the promise of justice. (More on this later.) In war, metal flies at high velocity through flesh. Just war becomes a question of targeting, conduct, and the consequences of victory.

So we are at a place in American art where laughing along with Pop's facile appearance, saved in our intellectual seriousness at the last second by ironic distance, just isn't going to cut it. Social consequences driven by culture have become too important. I've seen enough Skate videos in museums, thanks, and false landscapes that show an untouched nature, endless recyclings of Warhol (who of course was about endless recyclings), wise but safe sayings by famous poets engraved on cement benches.

Pop imagery hides too much, it's obsessively clean edges that serve like candy coatings on shapes, obscuring their nature of the image, making art inter-changable, commodity-like, endlessly distancing. Kiefer cuts the weeds from the path: release the dialectic between thought and emotion.

While looking for contacts with European artists about the B-17 project - I found this excellent interview with Anselm Kiefer by Sean O'Hagan, who more and more represents to me what art must be today.

His mentor was Joseph Beuys, who once famously explained art history to a dead rabbit in a three day gallery exhibition, and who later founded the German Green Party.

I am fond of artist interviews: art prose tends to be unreadable, either fawning, dry or cynical.

His show that toured through S.F. a couple years ago, the maddeningly ambitious, intelligent and emotional Heaven and Earth, is I think one of the great cultural works of contemporary art. It would have been easy for him to join the massed millions in the lightly ironic Pop Army, but he bucked every trend, progressive in politics, conservative of art's real power.

Below, O'Hagen describes paintings from my favorite series - monumental paintings of the open ocean - in Leviathan, a lead U-Boat hangs just above the sea. (One note here - I'm not sure that any artist's work looks worse on the internet than Kiefer's compared to its actual appearance. It will look muddy and scattered and unreadable in many of the images- this is emphatically NOT the case in person. )

Kiefer's sea is a huge, brooding ocean, grey-black, turbulent, thunderous. Up close, the crashing waves seem like solid ripples of congealed oil so thick are the layers of paint - and what looks like encrusted earth - that have been applied to the canvas. The paintings are so elemental, so humming with raw energy, that you can almost hear the ocean's roar in this big cavernous room. There are echoes, too, of other seascapes, of Turner, of course, and Courbet.

'Yes! Yes!' says Kiefer, nodding his head vigorously. 'You do the sea and Turner is there, always.' I ask him if, given his prodigious output, he discards many works along the way. 'Many, yes. But then I go over them. A painting is a conglomeration of failings. But, we can say this of life also.'

He laughs and then quickly turns serious again. 'The making of a painting,' he continues, 'is a reflection of your thought process but it also has a process of its own. Always, it is about somewhere I am trying to get to that I can never get to. This is the dilemma. But you also reach a place of transformation. The painting is transformed and you are transformed also. This is the exciting part.

Turner - that made me happy, it was my second thought looking at these pieces. The first was that it felt more like being on the sea that any painting I've ever seen .

In particular, he had delved deep into what it means to be German, and poked around in the open wounds from the War in order to find a path out of unimaginable horror, a horror which had to not just be confronted but engaged.

It is not a minor point that American artists must too regard our recent history with open eyes, and find a path to our best selves. We have an odder task than German artists. Americans would confront self-concept of heroism in that same, infinitely bloody war, and in present war. Superficially, that is easier.

But war by nature mixes heroism and brutality- the means which serve the hero and the villain were not greatly different. I read the account of one B-17 pilot who said, after much agonizing over the shift in targeting toward the destruction of cities, that there was one salvation for such horror: the promise of justice. (More on this later.) In war, metal flies at high velocity through flesh. Just war becomes a question of targeting, conduct, and the consequences of victory.

So we are at a place in American art where laughing along with Pop's facile appearance, saved in our intellectual seriousness at the last second by ironic distance, just isn't going to cut it. Social consequences driven by culture have become too important. I've seen enough Skate videos in museums, thanks, and false landscapes that show an untouched nature, endless recyclings of Warhol (who of course was about endless recyclings), wise but safe sayings by famous poets engraved on cement benches.

Pop imagery hides too much, it's obsessively clean edges that serve like candy coatings on shapes, obscuring their nature of the image, making art inter-changable, commodity-like, endlessly distancing. Kiefer cuts the weeds from the path: release the dialectic between thought and emotion.

Screwing Up Things is a Virtue: Death of Robert Rauschenberg

A leader in the first group of post-abstract expressionist artists who made American art leading in the world, along with Joseph Cornell, John Cage, Jasper Johns, and other artists whose names start with "J" rather than R, the great Robert Rauschenberg passes away.

His pieces were wildly uneven. Many are fantastic. Many don't work at all. This was necessary. It required failure, turning it into a distinct process, a word now so loaded among artists it's hard to see it's meaning clearly. Warhol was a johnny-come -lately to this group, and wrongly credited with the the revolutionary character that his elders actually deserved. Rauschenburg and the broader group was busy liberating all artists, and vastly expanding what American culture was, and what it taught the world.

From the New York Times.

The process — an improvisatory, counterintuitive way of doing things — was always what mattered most to him. “Screwing things up is a virtue,” he said when he was 74. “Being correct is never the point. I have an almost fanatically correct assistant, and by the time she re-spells my words and corrects my punctuation, I can’t read what I wrote. Being right can stop all the momentum of a very interesting idea.”

This attitude also inclined him, as the painter Jack Tworkov once said, “to see beyond what others have decided should be the limits of art. " He “keeps asking the question — and it’s a terrific question philosophically, whether or not the results are great art,” Tworkov said, “and his asking it has influenced a whole generation of artists.”

But I think it's bigger than that - the achievements of the Post-War American artists in general, and you have to not only include but feature jazz music in this period, took a devastated world, and began to examine every assumption about what art and culture is. Facing the related eradication of faith in old forms of culture (these old forms had after all, done next to nothing at to halt the rise of fascism - a crime of realism that is still unforgiven), they broke everything to see what was inside.

The Post-War American artists left art and culture confused, faithless, desperate, arrogant, humbled, full of errors, innumerable failures, unquenchable bullshit, and created the most vibrant period of art-making in all of human history, which would be now. That has permutations throughout the society. They are not minor. The fearful perceive this evolution as a culture war.

Much is owed to the men and women who freed us from fascism. Much is owed to artists who freed and expanded our minds afterwards, and helped build some of the cultural power that, under the guidance of fear-mongers, we have been pissing away like cheap beer.

The Lost Path of Another Century 2006

Paintings like Klimpt's Adele Bloch Bauer, (which sold for over 500 million dollars _ are hugely overvalued, and enormously under-appreciated. This painting was radical without abandoning any of its classical power; it shamelessly revels in visual beauty, and like the related The Kiss, has no doubt lead thousands of female freshman art history majors to their doom.

What is so extraordinary is not only the power of the portrait, but the smoothness and clarity transition between decoration and description, geometric pattern and mimetic space, portraiture and abstract pattern transformation, color structure, material surface, the extremely subtle indication of real light and space (using GOLD - which is an amazing degree of control) all without losing the liveliness of Adele.

I bring this up because I am wondering if any artist living today is allowed to love the world enough to paint like this. People frothing over with sentiment can't paint like this, nor can cynical post-modernists, or careerist poseurs. To learn to do this now would require an almost impossible pedagogy: becoming an absolute master classical of painting without falling into reactionary neo-Renaissance spit-wadding (ala Odd Nerdrum); you would have to be on the cutting edge of what is possible to do with art, let alone paint, yet not be ossified. This painting could not have resulted from revivalism or what I like to call the fetish of oils, which utterly misses the point of painting. Painting as the substantive, exploratory poetry of fine art is not crafty exhibitionism in an arty space, as many half-vast urban weekly appletini-besotted art critics seem to think.

To paint like this you would not only master observational drawing and anatomy but highly advanced decorative patterning, and then simply using that as a source for a far freer integration of complex, abstract compositional design into the pictural space. Jackasses cannot paint like this.

There is no monkey-mimesis here at all; Klimpt's visual intellect is totally active in all areas, and much, much more ambitiously, in their integration. It's something like putting the remorseless accuracy of Thomas Eakins into the compositional world of Matisse, adding the portrait and surface abilities of Sargent. His brilliant student, Egon Schiele, (caution: a bit naughty) refined the anatomical darkness pushing at the edges here, suggesting the fragility of the soft skin on bones, a little whiff of death wrapping around the sex, femininity in delicacy, time eating at the moment. But in Klimt, the whole scene radiates life, brightly and darkly.

You have to get far beyond it's initial dazzle and prettiness to see what it really is: a confident apex of faith in painting's essential sophistication and power. Executing this visual approach (as opposed to simply copying it or aping its style) with a new sitter and scene would humble me; and like I say, I'm not at all sure it is in the capability of anyone living now. We're too skittish, too fast, trained either to squirrel-ish uncertainty or unearned confidence, the latter from too much trend and market, the former from the maddening blizzard of disconnected greedy images we call a visual culture. Klimt could trust his painting methodology in a way I'm not sure is still possible, and that changes what it is possible to paint.

But what would I know? I spent the last two weeks trying to paint imaginary clouds.

This painting is tremendously valuable - not $135 million, nothing is, although it occurs to me it might take a million or twa to train and educate someone from the age of 10 to learn how to paint in this style. But the darker point is that while this gooey painting subtly incorporates the lessons of what I'm going to go ahead and call early modernism (a Cezanne-like space, unleashed expressive content,active negotiation with abstract design that pushes against its visual illusions, and allusions, for that matter), contemporary artists don't really see like this anymore, and when they come close, relearning illusionistic painting, they tend to become either reactionary, or redefine their work as an advanced kind of conceptual art, lots of fairly thin symbols standing in for intellectual concepts that are essentially literary, linguistic, or even mathematical rather than visual, as if vision, to which the majority of our brain is devoted, is anti-intellectual. After Marcel Duchamp over-famously denigrated "mere retinal experience" as a way of liberating himself from the constraints of painting, I'm not sure art ever recovered fully.

Few complain about beautiful language in service of intellectual ideas, but the bitching over visual beauty toward the same end never stops, because of the unsupportable and somewhat unexamined dominance of the word within the visual arts. Strange that in the midst of unprecendented artistic production, to sit down and examine a beloved person with inexhaustible visual intelligence may be the lost path of another century.

Tiananmen and The Power of Painting (2009)

NYT- A former solider at Tiannamen Square, later turned performance artist, goes back and paints what he saw, death, destruction, murder of the unarmed, and in particular, a roughly hacked off ponytail.

When people stop panicking themselves into a censorous froth about painting, I'll know painting is dead. But this keeps happening, and because of the personal nature of it, always will. The Venice Biennial's entry from Iceland gets to the same problem in the turgid contemporary art world- a meta-piece supposedly about painting, that secretly, is actually painting. Unfortunately, the painting isn't very good. Surprise!

I note that even in the New York Times, there was oddly no link to the direct images, in either story. The even, seamless, machine glaze of photography that equates all images keeps you nice and safe.

In the meantime, please enjoy and be horrified by the paintings of Zhi Lin, one of my grad school profs at UW, who has some experience of those years, and turned the curiously French academic style of Maoist era art instruction against the Chinese government murder of its own citizens protesting peacefully for democracy; people who were killed by the thousands, probably, without, I might add, any real help or more than formal protest from Bush 41. They had put up a STATUE of liberty, for god's sake-this moment was also a nadir in American history.

Update: I can't find the paintings on Google, or Bing, for that matter. This has me worried. Is Google pleasuring China's dictators yet again?

I think what I will do from now on: whenever China's leadership makes noises about reasonableness and capitalism and the earth's climate and Tibet, I will take a fresh look at Zhi's paintings, such as this fine work, "Capital Executions in China: Decapitation."

Note too, his newer work on early Chinese immigration in the U.S.

UPDATE #2

This repost yesterday of the NY Times story on Chen Guang included the thought the they hadn't actually published the paintings in any detail- I also wrote the reporter and received an interesting reply. But today, I cannot find any images in Google- or Bing for that matter -of Chen Guang's paintings of the Tianamen massacre, only references to the story and that single, very limited photo of the artist smoking- like you do.

Text of Letter Accompanying "Julianna" Painting 2009

Dear T.,

An old tradition in artist's letters is the description of the painting to those who buy significant works. This is an email, which seems wrong. Ah well.

This particular work was begun in the late summer of 2005 and finished early this year. The model was a very striking, 20 year old , 5' 10" gothy girl named Julianna who was planning to go to college for art, given to artfully torn clothing; like a lot of women with this style, she'd had some rough family history but a good high school education on the Olympic Peninsula. As ever, a punk rockish style thrives in the smaller towns and burbs among the alienated - Julianna was captivated by Victorian dreams and darkly toned independent rock music. Answering an ad on Craig's list , she was new to art modeling; she was poised, bright, and a little coltish.

(Admittedly that's the opening paragraph to a bad novel. )

As I think of her now, the painting was begun in my studio with her standing and posing towards the window on an unusual day where the sun penetrated to the blank wall in the window in the building, creating strong yellowish light in the upper right hand corner and backlighting her, with violet shadows in the room and a very warm cast on her normally pale and clear skin. She was quick -witted, curious and funny, with a playful self-consciousness about her style, but without much shyness Physically, she was tall, and trim and imposing, but very feminine in her frame, not over exercised or tanned or even tattooed, which is almost unusual for a girl like this now; and she was given to dark eyeliner, which taste aside, does indeed make light eyes haunting. The eyes are somewhat obscured in a lot of these pieces because they can easily over-dominate a composition.

She worked at the outdoor crepe cafe under the Washington State and Convention Center, where, visiting her once at her invitation (she made a great crepe- which I still remember, like one does when handed delicious food by a beautiful woman, belgian ham, fresh herbs and grueyre) I noticed at least four 20ish guys clearly coming there to talk to her, hanging out on any available pretense, because, presumably, they all really appreciated a good crepe.

We had about four or five sessions for this piece. Like a lot of women models, her first thoughts in a pose were of photographic style poses- artificial, sudden stillness. These I mostly ignored, waiting for more natural movement, slow walks, natural stillness, falling asleep on the couch. Drawing and painting is the act of becoming aware of what you see, of intently feeding the visual memory. In these series of works, I'm feeding a specific moment, somewhat charged, into a memory to chase in paint, sometimes, like this piece, over the course of years. You would not recognize her in any normal way from seeing the piece, but in spite of feeding its studied abstractions spinning off the act of seeing her into my memory of this moment, this painting could only be Julianna. If she stood in front of it again, you would absolutely know it was her- in the piece you can find a very particular form in her nose and mouth that permits recognition, but the piece is far more about what you might call her visual broadcast over time, the way a woman in motion warps the space around her in the mind of a man seeing her.

There are three basic poses that settled out from the sessions embodied in the work- only two of which are clearly visible, in the middle and on the right. Unlike some others, this painting was a particularly difficult struggle because I had not develop the techniques for finishing it when I began it - the difficulty comes because the type of marking shapes I make- somewhat Arshille Gorky-like , figurative in nature, only partly fit what I was seeing, and ultimately proved tricky to integrate with the light, shadow that was also spinning through the space of the painting (which is my studio at 1148 NW Leary in Ballard, #22). It took well over two hundred hours to complete, with approximately 6 posing hours. Like a novel, it takes great time and reflection to begin to understand a moment.

She posed a bit more than I could pay her for, and she thanked me for kindness at a tough moment. This is painting is the record of that time. Julianna, the last I know, moved to Arizona in early 2006.

An old tradition in artist's letters is the description of the painting to those who buy significant works. This is an email, which seems wrong. Ah well.

This particular work was begun in the late summer of 2005 and finished early this year. The model was a very striking, 20 year old , 5' 10" gothy girl named Julianna who was planning to go to college for art, given to artfully torn clothing; like a lot of women with this style, she'd had some rough family history but a good high school education on the Olympic Peninsula. As ever, a punk rockish style thrives in the smaller towns and burbs among the alienated - Julianna was captivated by Victorian dreams and darkly toned independent rock music. Answering an ad on Craig's list , she was new to art modeling; she was poised, bright, and a little coltish.

(Admittedly that's the opening paragraph to a bad novel. )

As I think of her now, the painting was begun in my studio with her standing and posing towards the window on an unusual day where the sun penetrated to the blank wall in the window in the building, creating strong yellowish light in the upper right hand corner and backlighting her, with violet shadows in the room and a very warm cast on her normally pale and clear skin. She was quick -witted, curious and funny, with a playful self-consciousness about her style, but without much shyness Physically, she was tall, and trim and imposing, but very feminine in her frame, not over exercised or tanned or even tattooed, which is almost unusual for a girl like this now; and she was given to dark eyeliner, which taste aside, does indeed make light eyes haunting. The eyes are somewhat obscured in a lot of these pieces because they can easily over-dominate a composition.

She worked at the outdoor crepe cafe under the Washington State and Convention Center, where, visiting her once at her invitation (she made a great crepe- which I still remember, like one does when handed delicious food by a beautiful woman, belgian ham, fresh herbs and grueyre) I noticed at least four 20ish guys clearly coming there to talk to her, hanging out on any available pretense, because, presumably, they all really appreciated a good crepe.

We had about four or five sessions for this piece. Like a lot of women models, her first thoughts in a pose were of photographic style poses- artificial, sudden stillness. These I mostly ignored, waiting for more natural movement, slow walks, natural stillness, falling asleep on the couch. Drawing and painting is the act of becoming aware of what you see, of intently feeding the visual memory. In these series of works, I'm feeding a specific moment, somewhat charged, into a memory to chase in paint, sometimes, like this piece, over the course of years. You would not recognize her in any normal way from seeing the piece, but in spite of feeding its studied abstractions spinning off the act of seeing her into my memory of this moment, this painting could only be Julianna. If she stood in front of it again, you would absolutely know it was her- in the piece you can find a very particular form in her nose and mouth that permits recognition, but the piece is far more about what you might call her visual broadcast over time, the way a woman in motion warps the space around her in the mind of a man seeing her.

There are three basic poses that settled out from the sessions embodied in the work- only two of which are clearly visible, in the middle and on the right. Unlike some others, this painting was a particularly difficult struggle because I had not develop the techniques for finishing it when I began it - the difficulty comes because the type of marking shapes I make- somewhat Arshille Gorky-like , figurative in nature, only partly fit what I was seeing, and ultimately proved tricky to integrate with the light, shadow that was also spinning through the space of the painting (which is my studio at 1148 NW Leary in Ballard, #22). It took well over two hundred hours to complete, with approximately 6 posing hours. Like a novel, it takes great time and reflection to begin to understand a moment.

She posed a bit more than I could pay her for, and she thanked me for kindness at a tough moment. This is painting is the record of that time. Julianna, the last I know, moved to Arizona in early 2006.

An Artist's Statement from 2010

These paintings developed from a figure drawing exercise where a model moves and new drawings at each movement are superimposed on the previous drawing. This idea of a still image as a description of the passage of time was famously used in Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, which itself was based in early strobe photography.

In my work, the direction is reversed; where the early moderns were embracing technology, metal, speed, time and gunning for the future, this work stuffs 20th century gestural abstraction back into observational painting traditions; the notion of time employed is organic and human, photography bypassed, the marks muscular but pushed into pictorial space.

I often start with a model, drawing in charcoal for several hours, building representative shapes and colors. Over months, I work on top of the drawings, painting based on what I saw, remember, and anticipated. Although these works appear abstract, most represent specific aspects of real people: observed colors, forms and shapes, paying careful attention to integrating the disparate elements into a coherent whole- usually one that also implies a kind of re-generating landscape in which the figures exist.

To simply understand the physical, temporal, visual, and emotional presence of another person in the same room is a rich problem with no simple paradigm, and painting is well suited to juggling the different aspects of this inexhaustible complexity.

Pushing around the mud to chase the temporal and solidify the ephemeral, I embrace painting traditions, but painting is art to the extent that it continues to create art. This most ancient of media, almost a shelter in the blizzard of pop images, provides unique processes for the exploration of our nature as visual thinkers, as identities and cultures, as breathing, bleeding creatures struggling to be fully conscious of their time and place. My paintings argue that within the nexus of vision, material, illusion and the painting process itself is an irreplaceable process for understanding, in Gauguin’s phrase, where we come from, what we are, where are we go

ing – questions too beautiful for comfort.

In my work, the direction is reversed; where the early moderns were embracing technology, metal, speed, time and gunning for the future, this work stuffs 20th century gestural abstraction back into observational painting traditions; the notion of time employed is organic and human, photography bypassed, the marks muscular but pushed into pictorial space.

I often start with a model, drawing in charcoal for several hours, building representative shapes and colors. Over months, I work on top of the drawings, painting based on what I saw, remember, and anticipated. Although these works appear abstract, most represent specific aspects of real people: observed colors, forms and shapes, paying careful attention to integrating the disparate elements into a coherent whole- usually one that also implies a kind of re-generating landscape in which the figures exist.

To simply understand the physical, temporal, visual, and emotional presence of another person in the same room is a rich problem with no simple paradigm, and painting is well suited to juggling the different aspects of this inexhaustible complexity.

Pushing around the mud to chase the temporal and solidify the ephemeral, I embrace painting traditions, but painting is art to the extent that it continues to create art. This most ancient of media, almost a shelter in the blizzard of pop images, provides unique processes for the exploration of our nature as visual thinkers, as identities and cultures, as breathing, bleeding creatures struggling to be fully conscious of their time and place. My paintings argue that within the nexus of vision, material, illusion and the painting process itself is an irreplaceable process for understanding, in Gauguin’s phrase, where we come from, what we are, where are we go

ing – questions too beautiful for comfort.

Saturday, January 16, 2010

Friday, January 08, 2010

Thursday, January 07, 2010

Friday, June 05, 2009

Saturday, June 28, 2008

A Dark Passage

(Click on the image to enlarge)

(Click on the image to enlarge) A canvas that I started working way back in 2001, this did not really begin to develop until last year, when I drove toward a strong classical illusion of light and dark, but only in service of mood. This image is wholly invented, and is to me a logical extension of abstract expressionist techniques. I simply kept driving until a landscape slowly emerge, populated with Arshile Gorky-like figurative lines stuffed back into specific allocations of space. The color and light in the impossible sky (no moonlight and sunrise would work like this) is verging dangerously on the surreal, but I'm not exploring a subconscious dream-image world, or front-loading an image with a sense of the internal purity of the subconscious.

I hope that the mood emerges naturally; if there is any specific referent (and this is a recurrent theme) it is that in the midst of the contemplation of emptiness, it is impossible not to want to see people, but our experience of this, while emotionally strong, is visually fleeting, always in motion, always just beyond grasp.

Are the swirling lines and forms sinking into and out of the dark gendered? Yes - you can think of a Picasso line, it's weight turning and twisting and surprisingly sexualized even while dissociated from body-but this is one way somewhat incidental to the work of the painting. Virtually all the work was the invention of the space, light and landscape. But I do think that the implication of imagined figures and imagined place is balanced on viewing the piece.

Saturday, February 23, 2008

The Everything Painting

Click on Image to Enlarge

This still-untitled work is in oil, about 60" by 84", and began with my most traditional process of two or three sessions with a model. Like the last major painting, there is a distinct implication of perspectival and atmospheric distance that the figurative forms occupy. Here, the connection to a real person, and a much more specifically conceived invented landscape are more apparent.

I am flirting with surrealism here, not to mention eroticism, but these evolved out of working with it. To me, it's closest affinity is with Excavation, by DeKooning. It has the same figurative sources, the same push to all-over abstracted form tiling, but re-embraces classical painting spatiality.

Which may be why these are taking so long - I have to decide where every abstract bit hangs in space, without much of a mimetic guide other than skin in light and shadow, and there almost no sketches. It was worked like a high modernism - trial and error, excavating the form.

The model's relationship to the image grew particularly stretched in terms of imagery, but her compositional positions were critical and largely survived. I have several earlier versions I may post later.

This working title of "The Everything Painting" is due to it's somewhat hopeless attempt to find a sweet spot between figurative realism, all-over abstraction, classical landscape (there is an ocean and a ground and a distant mountain range under there) and I'm afraid to say surrealism, in the sense at least of dream imagery. I generally dislike surrealism, with the exception of Yves Tanguy, because it tends to feel false and forced to me.

What I do like is any painting that successfully creates an embracing idea-atmosphere, where the emotions and the logic of the work are inseparable, powerful, and specific to the terms of painting.

Julianna in the Near Final Version

Click on image to enlarge

Click on image to enlargeThis is the near final version of Julianna, o/c 60" by 42", originally posted below.

Sorry for the image quality -to be improved on most of these soon.

Moving to Private Collection

Anchorage, Alaska

Anchorage, Alaska

A Ferocious Collage - Island in Water, Island of Water

This is a medium size collage made from about 125 landscape paintings, intent on wrapping the horizon line around, which creates an atmospheric and perspectival infinity all around the edges, and in the middle.

Might turn into a major painting.

Thursday, November 08, 2007

Jamie Bollenbach Main Website

I'm building a new web site here, which features the work using slide show software, as well as links to my teaching syllabi, professional and contact information, and a 2004 interview.

Thursday, November 01, 2007

Jamie Bollenbach at MyArtSpace

Many of these works and some others are located in web gallery format here.

Friday, June 01, 2007

New Work, in Progress

(Click for larger image.)

This largish piece (about 60" by 48" currently untitled) has been consuming me for some months - it's an older work I've repainted innumerable times since it was begun in late 2005. The original subject is a model named Julianna, who posed for about three sessions at that time. No photos, video or digital manipulations were used.

The problem here lurks under the surface of all my post-2002 work: how do a series of related images occupy the same space without simply being juxtaposed? I'm trying to integrate the paint marks - which can indicate space or light on, behind, next to or in front of my memory of the model, with each other, getting them to flow naturally into one another - the effect is somewhat pointillistic, but the issue is not accurate light and color, but rather the inconsistent way light and color on the figure are both preserved and distorted by memory.

A loose, more or less modernist aesthetic interpretation governs most of the day to day painting choices.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Population

Population, oil on canvas aprox. 37" by 50". (c) 2006 Jamie Bollenbach All rights reserved.

Population, oil on canvas aprox. 37" by 50". (c) 2006 Jamie Bollenbach All rights reserved.This is two or three months of difficult work, done very inefficiently, without planning sketches: a technical summary of the last four years, either the beginning or end of something. Horror vacui if ever there was - but the operational idea is simply spatial shapes transforming into shapes with figurative referents. There is a lot of deep space and compositional movements across the collections of shapes. With no model, it's somewhat emotionless in execution, although it should be unsettling in terms of where the viewer is, and whether the subject really has anything to do with a person, or a landscape. Primarily, it pushes the evolution of these marks into the horizon, into darkness, into grey space until they disappear. The vision's desire to resolve these into people keeps the eye moving, scanning, so that it is difficult to see the piece as a single image. That means the image must be "read" over a period of time rather than recognized as a solitary symbol.

I'm interested in the way a painting can specifically portray time by direct manipulation of images, and surface properties, which imply time, and relate to the passage of time in the making of the image itself: the strange balance of paintings, particularly portraiture, that photograhy or paintings of photography tend to lack.

Influential to this was a desire to do the equivalent of treating a Willem DeKooning in three dimensions, with something like real light (but without a distinct source.) Related work, but not directly influential, is with early Marcel Duchamp, the Futurists, cubism (well, that covers both the fascists and the communists) in the attempt to tackle time, and surrealist Yves Tanguy with precise surface qualities of unreal objects: an objective treatment of the non-objective.

Collection of the Artist. Available.

Friday, April 14, 2006

Comparisons

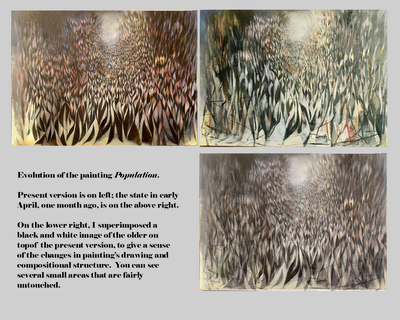

Working Title: Population

Working Title: Population2006, o/c

This my primary working painting for the last two months, still in process. It has only grown more and more complex, absorbing each mark and demanding reactions. I'm thinking of it as something like a Excavation by Dekooning, but treated in classical dimensions. (It has also been described lightly as Nude Descending a Hell of a Lot of Staircases. )

This painting is the end of a certain composition I have used for a while, and I suspect the beginning of a substantial shift in my work.

It has changed substantially in the last two weeks, particularly in the lower third, and on the upper left; the distant center, detail below, has changed somewhat less.

Sara #27 2005 o/c 24" x 40"

This piece was sourced directly from a set of poses by Sara, over about 3 sessions in June 2005 - it's dark to allow a great variance in transparency, and to create a strong illusion of piercing lines of light. I particularly like the dimensionality of the fluttering small collection of marks around the primary figure off to the right.

This piece was sourced directly from a set of poses by Sara, over about 3 sessions in June 2005 - it's dark to allow a great variance in transparency, and to create a strong illusion of piercing lines of light. I particularly like the dimensionality of the fluttering small collection of marks around the primary figure off to the right.It's reactive rather than planned; I became more and more interested in making transparent marks - like wholly disconnected areas of highlights hitting skin, flicking around in all directions. This painting was a significant advance, one of my favorites.

Collection of Mark Vadon and Mattie Iverson.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)